Stories of Impact

Back to In Action / Antonio Gamboa, Educator

Antonio Gamboa

Science Teacher at Garey High School, Pomona, CA

Antonio Gamboa has been a Science Teacher in the Pomona Unified School District for the last 18 years. He teaches biology, physics, and chemistry to 8th-12th graders of varying aptitudes and backgrounds (ELL, Special Education, valedictorians).

The majority of his students are of Hispanic origin and qualify for free and reduced lunch.

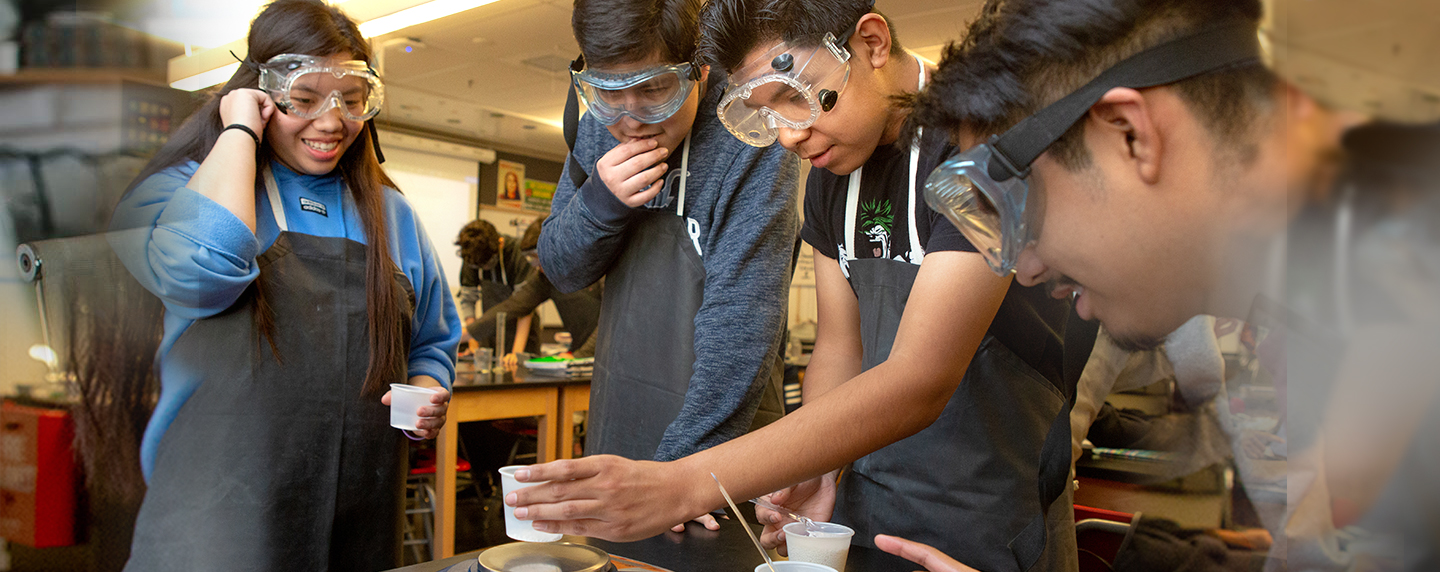

Students in Antonio Gamboa's classroom.

Their immediate response and level of engagement when they started thinking ‘I can invent something’…that got my attention.

How did you come across Invention Education?

I’d been receiving emails from the Lemelson-MIT Program for a couple of years, inviting me to participate in their InvenTeams. Every time I’d see the email I’d think ‘I don’t think I can do this. The students can’t do this.’ I’ve been involved in science fairs and different projects, so it’s not like I was a teacher who was not involved. I was very involved. It just seemed too out of reach.

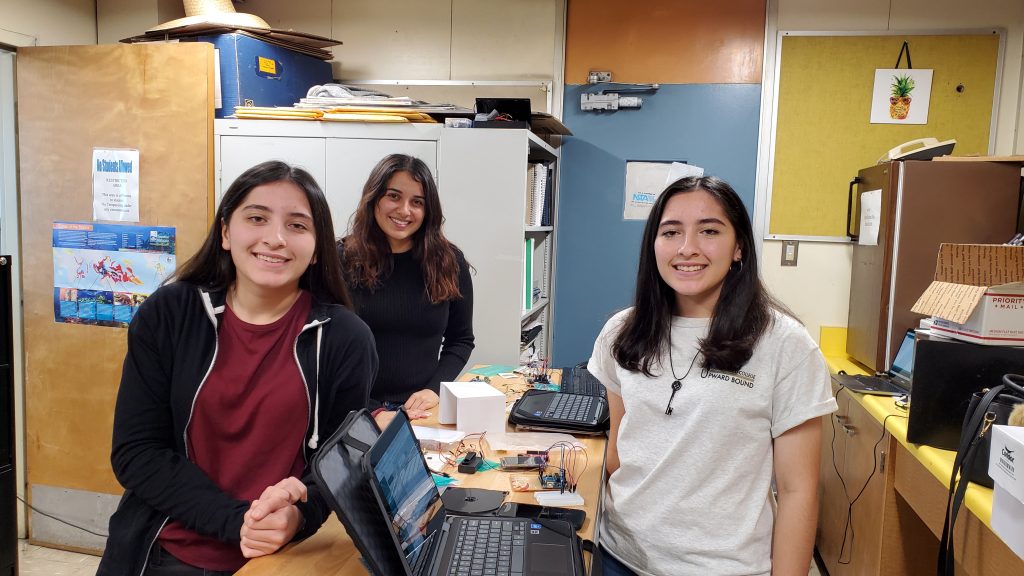

One day after school, in 2017, I was in my classroom, checking email. There were three 10th grade girls behind me, going over things on the board. I saw that I’d received yet another email from Lemelson-MIT. I spontaneously said out loud ‘They want me to invent something?! I’m not inventing anything! That’s it! I’m not doing it!’ One of the students, when she overheard me, turned around and said ‘I want to invent something.’ I looked at her and said, ‘Oh really? You want to invent something?’ in my mind thinking ‘Yeah, sure, everyone can just invent something. Ha!’ So I asked her what she wanted to invent and she immediately began talking about something with shoelaces and the other students started getting engaged. Their immediate response and level of engagement when they started thinking ‘I can invent something’…that got my attention.

So you finally responded to Lemelson-MIT?

Not exactly. Back then, I thought there was no way I could invent something. I thought an invention is something you just stumbled upon. I didn’t think invention is a process that can be learned or taught. I thought you had to be very very super smart. I told that student who said ‘I want to invent something’ that I would share the Lemelson-MIT email with her and if she could come up with the answers to the questions they were asking me (including a video), I would think about it.

That evening she sent me everything Lemelson-MIT was asking for.

Wow. That’s amazing.

Yes. So I kept my word and went to the first teacher orientation for Lemelson-MIT’s InvenTeams. But I was still of the mind that I wasn’t going to do the program. It was a lot of work and I couldn’t imagine where I was going to get the students who wanted to invent.

Even though a teacher who had already done it assured me that it was not what I thought it was and encouraged me to go for it, I still wasn’t sold.

When I came back, I sent the orientation materials and next steps to the student who was encouraging me to keep going. I told her if she wants us to move forward, she has to take the lead. She has to find a team. I was doing a summer program in Illinois. I wasn’t going to be back in California until August and Lemelson-MIT needed everything by October. I was clear that this was on her. Mind you, she was bright, but an average student.

That summer, she independently set up interviews and recruited a team.

So I finally got on board, but I told them: ‘I’m not going to be your teacher. I’m not an inventor. I’m going to be your mentor. I’m going to help you get through it. That means I’m here to guide you, help you out when you’re in trouble. But I can’t tell you what to invent. I can’t give you the ideas. It has to come from you.’

What made it so motivating for the students?

I think that what happens is that in these communities there is such a need to follow rules. It is a culture of constraints. ‘I don’t have the money’, ‘I can’t go any place’. Their parents have very limited resources. Some of them live in very small places. And with invention, all of a sudden they have the opportunity to say ‘What if?’ and to really let their minds go wild with possibilities about what could be. It’s an outlet for them to think about things differently and how they can make them better.

And now having been through the process with students a few times, I can tell you, it’s not the top ten students that find the most success. Once students realize that there is not a right or wrong answer, that it’s just a process that you give yourself over to, they relax because they finally have an outlet to fail in a safe way. That opportunity doesn’t seem to be present in most of their classes or in their lives. It’s a way to see themselves differently – that they can have original ideas about things they care about and can apply them. Then within a team, it becomes clear that it’s not just one skill set that is needed. You need many to invent and inevitably, there is a place for everyone’s talents.

How did you ultimately incorporate Invention Education into your teaching practice?

For the initial InvenTeams, it was students from my class that made up the team, so I started giving them time during class. Then we started having meetings after school.

Ultimately, when I saw how engaged the students were and how much they were getting out of it, I knew it needed to be more than a club. It needed to be integrated into the formal school day. So we created a zero period – which does not conflict with any other classes – to teach a class with the goal of inventing and developing an inventor’s way of thinking. We had to integrate it into a science class that was already approved, so we chose AP Environmental Science. We believed that there would be lots of ways to tie Environmental Science to invention. We thought making it an AP, which comes with extra credit, would add incentive for students to join. We take students through the expected AP Environmental Science curriculum, and prepare them well for the AP exam, but we do that while setting aside the same day each week (Friday) to take students through the invention process, tying in subject matter expertise they are gaining from the rest of class.

Did you face any challenges when you first began to integrate it into your teaching? And if so, how did you overcome them?

My biggest challenge was my own self-perception and my perception of what it means to and who can invent.

Once I got over that, it wasn’t really a challenge for me to integrate Invention Education into teaching. I had already successfully integrated science fair projects into my curriculum and used a similar model with invention.

What has been the impact of Invention Education on your students? What if any changes have you seen in them?

Since introducing Invention Education, we’ve seen tremendous growth of student interest in science. In the most recent graduating class, 15 females intend to pursue STEM education and careers. We’ve never seen anything like that before. And not all of them were even in my class! When I asked one girl, not in my class, why she made this choice, she said: InvenTeams. She was so inspired by their example. I was shocked.

Especially for girls, we see their confidence level become so high. They see that the invention process is not about traditional measures of being “smart”. They come to appreciate who they are as individual thinkers, collaborators and contributors.

They realize science and STEM have something to offer them. Science is not what they thought; it’s not just men in lab coats. It’s a way to help the community and make something better. We never push girls into science. Instead, we let them experience it, apply it and the rest happens organically.

What are some of the skill sets that a student builds within an Invention Education setting and what are some that they bring to bear?

They realize failure is absolutely ok and necessary. They are no longer afraid of it. In fact, they realize that trying, failing and trying again as many times as you need to will lead to something better. They also learn collaboration skills. They see they can’t achieve the best outcome alone. Finally, they learn how to communicate with each other. It’s not uncommon for team members to get mad at each other, but they learn to resolve disagreements for the good of the team.

The only thing students need to bring to an Invention Education setting is a willingness to learn, try and commit the time.

How has the incorporation of Invention Education impacted your teaching practice, and you personally?

Invention Education has transformed my teaching practice. I’ve realized that invention is a process that inspires student engagement. It motivates them to go to college. I’ve never seen anything like it before.

What has been the reaction of administrators to the integration of Invention Education into your classroom? Has your work prompted an interest in expanding access within your school and/or the district?

Initially the administration was excited about the name “MIT”. But the real excitement started when they saw students reaching out to the community, and presenting and speaking at the community center downtown. When they started making videos and appearing in the newspaper. It exceeded their expectations.

As momentum grew, we started talking with the district, who ended up supporting us tremendously with equipment. We even formed a team to develop science education curriculum across the district, to introduce robotics, to collaborate with the middle school.

It has changed the way the district looks at science. Initially the district was not supportive of science fairs. Now the district has its own science fair with medals, trophies, and a big event.

What advice would you give to teachers who are new to Invention Education and are trying to figure out where to begin?

Now that I have done it, and been through the process, I see that a lot of teachers believe, as I did a few years back, that it requires a higher level of thinking. They perceive inventors as being so high up there, out of reach. They believe “There is no way it’s going to happen in high school and there is no way it’s going to happen to me.”

It’s not true. You are not expected to have all the answers. You become a facilitator. Your role is to help students figure out the answers for themselves, regardless if the invention ever comes to fruition. Teachers have to be willing to make that shift and to understand the students transform you as much as you transform them.

For a new teacher especially, it’s essential for them to understand how they can continue growing in the classroom, as an individual. To become a better teacher, you must allow your students to help you grow. You must allow them to be part of that process. Invention Education is probably the best way I’ve seen this happen. You will discover some of your own failures and talents you didn’t know you had. Same with your students. Talents will emerge that you never saw before.