Stories of Impact

Back to In Action / Rory Cooper, Educator

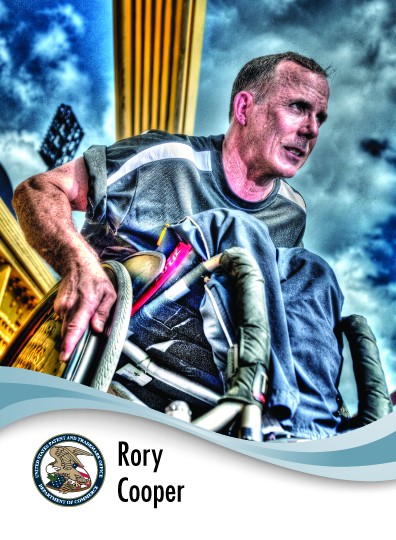

Rory Cooper

Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

Dr. Rory Cooper is the founder and director of the Human Engineering Research Laboratories. A U.S. Army veteran, Dr. Cooper has been designing assistive technology since a spinal cord injury during his military service left him partially paralyzed.

If you use a wheelchair or know someone who does, chances are it includes technology invented by Dr. Cooper. His inventions have been life-enabling for millions of people.

Part of what drives him is the Army’s core value of selfless service. “I wouldn’t be true to the oath I swore if I didn’t try to correct some injustice and create opportunity,” he said. The Human Engineering Research Laboratories he heads up is in fact a partnership between the University of Pittsburgh and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

He holds multiple patents, and in 2019, he joined the ranks of Ellen Ochoa, Nikola Tesla and others when he received his own inventor trading card from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Whether he’s inventing in his lab or meeting with lawmakers on Capitol Hill, Dr. Cooper — who is also a Paralympic medalist — is committed to using his experience and expertise to advocate for people with disabilities.

Dr. Rory A. Cooper is an engineer, a veteran, an athlete and the holder of more than 20 groundbreaking patents in wheelchair and other assistive technology

I think that homogeneity is the enemy of innovation. You need diversity in all its forms in order to be successful. It’s an economic imperative.

Tell us about your work.

I create technologies to help veterans and people with disabilities live life to the fullest. That is, return to work, go to school, have mobility, exercise and play. My inventions span a range of domains, from everyday wheelchairs to wheelchairs for sports to medical robots that help people eat and get in and out of bed.

What drew you to bioengineering? Were you into robots as a kid?

I was more into motorcycles. I was lucky — my grandparents, my mother and my father were all automotive machinists. We lived near Los Angeles and we had a family automotive shop. We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had a lot of talents. I made and modified my own skateboards, bicycles and motorcycles when I was a kid.

At age 20 you sustained a spinal cord injury. How did that shape your path to invention?

I joined the army at age 17 and unfortunately I was in an accident a few years later. So I had to leave, but the VA helped put me through college. Engineering seemed like a natural thing to do, so I enrolled at California Polytechnic State University. I got into inventing because the wheelchairs at the rehab hospital had not changed, or had changed very little, from the wheelchairs that veterans received during World War II. So I started making my own chairs. Then in grad school at the University of California, Santa Barbara, I discovered the field of rehabilitation engineering. And that launched me into continuing my work inventing things.

What challenges did you face along the way?

Lack of money was one challenge. The other challenge was that in academia, the emphasis was more on publishing rather than inventing. That finally changed around 2010, when universities started to realize that they probably could do a better job of technology transfer if they place greater emphasis on inventing, patenting and licensing.

Speaking of patents, you have 25 in wheelchair technology. Any favorites?

The Ergonomic Dual Surface Wheelchair Push Rim is one of the cooler patents. It’s a push rim designed to relieve stress on the user’s upper body. I use it myself, actually. In college I invented a tool called the smart wheel to improve my racing. But then I learned that carpal tunnel syndrome and rotator cuff injuries were prevalent among wheelchair users, so I started studying ergonomics and biomechanics. I realized the smart wheel could help prevent those injuries by gauging the amount of strain that the wheelchair design, set-up and its push rim is putting on a person’s body. Another one is the variable compliance joystick with compensation algorithm, a customizable device that can dramatically open up the possibilities for someone with limited mobility, from driving their own powered wheelchair to playing team sports such as powered soccer.

Everybody with a disability should have access to technology that can be life-changing and life-affirming.

What kind of impact have you seen through your work?

These are huge breakthroughs for people with disabilities. We’re helping people avoid surgery for injuries caused by using wheelchairs that could cost $30,000 to $50,000. So these innovations are saving the healthcare system a lot of money. But the main thing is what they do for the people who use them. The rate of carpal tunnel and rotator cuff injuries experienced by wheelchair users within five years of usage decreased from about 80% to about 20%. My wife is a physical therapist, and many of her patients use my technology. They tell her that it has changed their lives or their loved ones’ lives. My inventions have never made me a lot of money, but I have been paid more in smiles and happy tears than most inventors ever have.

How much did your own experience inform these inventions?

A tremendous amount. Though I work with a great team and a large network of people. We’re not just trying to solve my problems, because that would be very selfish. But I am so fortunate to be a veteran and to work with great people, including veterans. They have an embedded sense of service and they are willing to make themselves guinea pigs to help other veterans and other people. Veterans are often early adopters of technology, so they’re great at participating in research and giving candid feedback, which you want if your goal is to try to improve people’s lives. Everybody with a disability should have access to technology that can be life-changing and life-affirming. And there’s no one more deserving than somebody who’s sacrificed for their country.

In July you spoke to members of Congress on the importance of diversity. What was your message, and why do you think it’s important for invention?

I think that homogeneity is the enemy of innovation. You need diversity in all its forms in order to be successful. It’s an economic imperative. Raising the number of women inventors would have a significant impact on U.S. invention. And people from lower socioeconomic areas have less opportunity. I’m lucky, I was one of those who broke out. But there’s many more who didn’t, and that’s a huge loss. So if I can educate Congress on some of the barriers that I faced, and we can remove some of them, we’d all be better off.

How can higher education institutions encourage more invention and more entrepreneurship?

They have to make college more affordable and accessible. It should be about impact, not the number of dollars being brought in. We have to make sure that we address those smaller populations where we can have a big impact.

On your path to becoming an inventor, what was important for you in terms of support and overcoming challenges?

Everybody with a disability faces the challenge of how people perceive you, what you’re capable of doing. I face that to this day in various ways. And there are physical barriers, though they have been significantly reduced. Before the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990, it was very difficult to fly, rent a car, get a credit card, buy a home loan or land a job. Frankly, the work that I do is in some ways a challenge to convince people that older people and people with disabilities have value.

What role do you think inventors play today in solving global challenges as well as problems that affect specific communities?

I think they play an essential role. Somebody needs to translate scientific discoveries into practical solutions, and that’s essentially what inventors do. That’s what a patent is. It has to have novelty and utility. If it can solve a difficult problem, it’s probably got a high degree of novelty.

Any parting advice for aspiring inventors?

Tenacity, perseverance and hard work are really important traits. So is listening and being able to synthesize. It has been said that science happens at the intersections. That’s true of invention, too. I think I got to where I am today because of the relationships that I formed in the military and sports and with other inventors and scientists. So be part of a diverse network. Learn from other people. Hard problems are hard for a reason. And there are more hard problems in the world than there are easy ones.